Anne Tourney

There are still some parts of this country, mostly in its biblically belted waist, where your mother will yank you out of town once you get your white shoes dirty. It doesn't matter what you tell her, if your rosy lips were made to spill the truth. That old rule about wearing white shoes before Labor Day doesn’t make a damn bit of difference. You don’t want to wear those Sunday school shoes, you never wanted to wear those shoes. Anyway, those white shoes will be filthy the moment they touch your slutty feet.

There are still some parts of this country, mostly in its biblically belted waist, where your mother will yank you out of town once you get your white shoes dirty. It doesn't matter what you tell her, if your rosy lips were made to spill the truth. That old rule about wearing white shoes before Labor Day doesn’t make a damn bit of difference. You don’t want to wear those Sunday school shoes, you never wanted to wear those shoes. Anyway, those white shoes will be filthy the moment they touch your slutty feet.

Back in the Reaganite 80’s, when I was a teenager, late August was the sweltering armpit of every Bible Belt summer. Outdoors, the air sizzled with the whir and whine of bugs; indoors, tired air conditioners leaked a cool, thin trickle through the density of heat. Sitting cross-legged on the floor in front of the television, my thighs sticky with juice from the plate of watermelon I held in my lap, I spent way too many hours watching TV as I brooded over the encroaching First Day of School.

Yes, I watched soap operas in those days. And sitcoms. And family dramas. But my secret obsession was The Christian Broadcasting Network, a channel that filtered the news of the world, and the news of the soul, through a lens of Christianity, specifically the 20th-century, neo-conservative, Reaganized version of the faith. I spent hours with my eyes glued to CBN, not for the news broadcasts or the more mainstream talk shows, but for the electrified, revival tent contingent of preachers and singers, saviors and sinners. The soap stars had nothing on Tammy Faye and Jim Bakker of The PTL Club, and the dramas played out on Days of Our Lives or All My Children were yawn-worthy compared to the visions of impending apocalyptic doom (the year 2000 was right around the corner, and the Book of Revelation was getting a workout).

neo-conservative, Reaganized version of the faith. I spent hours with my eyes glued to CBN, not for the news broadcasts or the more mainstream talk shows, but for the electrified, revival tent contingent of preachers and singers, saviors and sinners. The soap stars had nothing on Tammy Faye and Jim Bakker of The PTL Club, and the dramas played out on Days of Our Lives or All My Children were yawn-worthy compared to the visions of impending apocalyptic doom (the year 2000 was right around the corner, and the Book of Revelation was getting a workout).

Then there were the dirty rumors that started cropping up in the secular media about Jim Bakker’s financial and sexual excesses, and Jimmy Swaggart’s soft spot for hookers. When the rumors proved to be true, the tearful public confessions that followed were equally lurid, and way more difficult to believe.

I haven’t thought about them in years, those smooth-talking, impeccably coiffed men of God, with their manicured hands and chunky rings, their pricey suits and their bulging real estate portfolios, their tenderly supportive wives and surgically enhanced secretaries. When Tammy Faye Bakker died last month, photos of her before and after cancer brought that world back into my consciousness. The emaciated, sallow woman of July 2007 was a specter of the buxom, unapologetically tacky televangelista who belted out Gospel songs while batting eyelashes that do a tarantula proud.

Though my family didn’t practice an evangelical version of Christianity, my childhood was steeped in a culture shaped by a Fundamentalist interpretation of the Bible. Even as a teen, I was never able to understand how the Son of God, supposedly the tangible manifestation of an incomprehen sibly vast divine love, could be held up as a wrathful homophobic, or how the Gospel could be used as a stick to beat sinners with, by men who did some pretty hefty sinning, themselves. Salvation is at your fingertips, the televangelists declared, redemption is just a few crocodile tears away, and yes, eternal life can be yours—if you’re a clean-cut Christian with a clear complexion and a bright n’ shiny heterosexual lifestyle.

sibly vast divine love, could be held up as a wrathful homophobic, or how the Gospel could be used as a stick to beat sinners with, by men who did some pretty hefty sinning, themselves. Salvation is at your fingertips, the televangelists declared, redemption is just a few crocodile tears away, and yes, eternal life can be yours—if you’re a clean-cut Christian with a clear complexion and a bright n’ shiny heterosexual lifestyle.

Over time I’ve tried to write my way through those violently mixed messages, not so much to reach an understanding of the spiritual life of the Religious Right, but to reach my own reconciliation of Christianity—the faith I still identify with—and my ever-overactive sexual imagination:

In your dirty white shoes, you stroll out to the edges of town, out past the shoulder of the highway, up toward the hills. It's one of those dream-walks. Your panties are soaked, and the heels of your shoes sink into the earth. Cars edge you onto the dark side of the road, alarming you with lights and horns, but you don't stop walking. You squat down to relieve yourself, and you know that your hot pee is going to yellow those heels the way it used to stain the snow behind your back porch (your brother could write his entire name in urine; it wasn't your fault that your physiology allowed only a dribble).

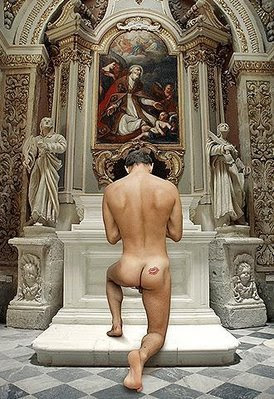

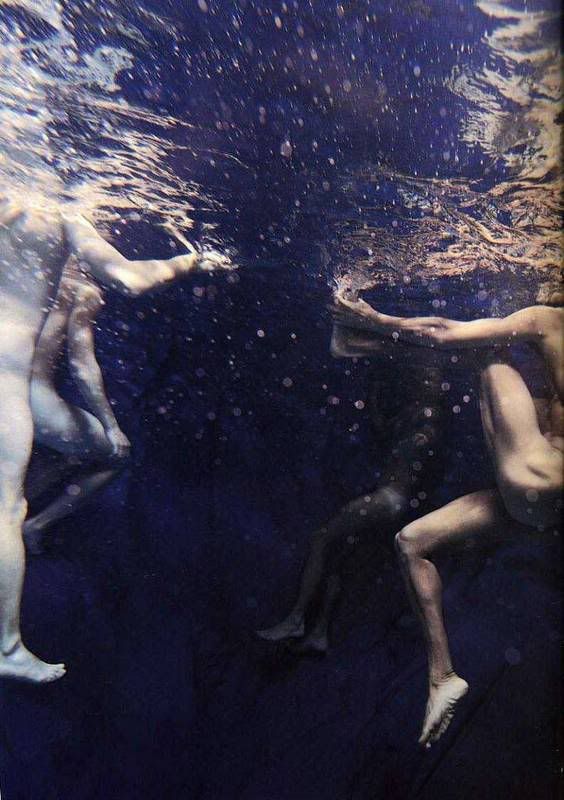

But it wasn’t just the sleaze, the sensationalism, or the outright lies that fascinated me. Quite the contrary—somewhere, in my timid adolescent soul, fed on a crunchy blend of secular skepticism and Episcopal doctrine—I was drawn to the idea of giving myself to Jesus, with some preacher as my intermediary, holding me underwater, shaping my transformation, helping me come to Christ. I longed for that climactic surrender, and the afterglow of acceptance that would follow.

I’d always known, from the time I was a child, that I was “bad.” Or “dirty.” I wasn’t sure why, but in the televangelists, I found confirmation that yes, human nature was intrinsically sexual, craven, lustful, and downright filthy. I’d always known that to be the case; I just wondered why bad had to be equated with wrong. I wasn’t quite sure what “sodomy” entailed, at the age of sixteen, but I had an uneasy feeling that I might have inadvertently done it, and that I should probably confess to it, just in case. Though I was drawn to the idea of being relieved of my sins through confession, conversion, and salvation, I always suspected th at the relationship between sexuality and divinity was far too deep and vast to be reigned in by the moral fences of the Religious Right (did you ever notice that those white picket fences are reinforced by concertina wire?).

at the relationship between sexuality and divinity was far too deep and vast to be reigned in by the moral fences of the Religious Right (did you ever notice that those white picket fences are reinforced by concertina wire?).

You don't feel Jesus glaring down on you when the boy's two fingers make you wriggle and scream, or when he scalds your thighs with his hot milk. But somehow, in your own backwards vision of the way salvation works, you feel Jesus arrive on the scene when your boyfriend hunkers down under the car seat, shoves your panties to one side with his thumb, and lovingly begins to chew your pussy. You hear the church choir singing "Nearer My God to Thee" when your thighs start to tremble, and your hips thrust up the pelvic offering plate of their own accord, and your clit peaks to steeple height.

What was it about those evangelical preachers that made me squirm with an uneasy mix of revulsion and teenage lust? I have to admit, I was seduced the easy tenderness of their emotions, their cloyingly mellow voices, their willingness to bare their hearts, whether it was in responding to the testimony of some wayward convert, or in confessing their own sins. With all the intimacy of the bedroom, they confessed and prayed and shared and felt in front of millions. They raised their hands to the sky, they closed their eyes in ecstasy, they moaned, they writhed. The ultimate in evangelical emotionalism occurred during the conversion experience, through the great spiritual release of “being saved." Coming to Jesus . . . really, can that choice of words be a coincidence?

According to the sweaty preacher in the tight polyester slacks, salvation was as simple as having Jesus Christ belly up to the local ice-cream bar and pay for your pineapple sundae before you even know you want it. But would Jesus still buy your sundae if he knew that your best friend gave you a crashing waterfall of an orgasm with the eraser of a Number Two pencil? You tend to suspect Jesus might have had more painful things on his mind than the orgasms of a girl who wouldn't be born for a couple of thousand more years, what with the Philistines berating him and his disciples denying him, and a crucifix bearing down on his shoulders.

I was baptized and confirmed in the Episcopal church, and in my observant phases, I spent my Sunday mornings in the cool, classically beautiful chapel of Trinity Episcopal. Episcopalian men didn’t cry, not because they weren’t emotionally liberated, but because any emotions experienced in a worship setting were usually too subtle, or were contained by a pressed, three-piece suit. (“Oh! Was that an epiphany I just experienced? Why yes, I do believe it was.”) With our sedate general public confession and our careful progression through the sacraments, we weren’t in any danger of experiencing orgasmic, ecstatic revelations of divine magnitude.

There was a certain sensual tenderness about the televangelists that attracted me, too. Trembling lips, silky waved hair, soft chins and hands . . . something intrinsically feminine about their personae. Yet at any time, they could call on the hard truth of Fundamentalism, the rigid dichotomies between right and wrong, good and evil. Counterbalancing that effeminate tenderness were the harsh, self-righteous wrath, the heat of the apocalypse, the dramatic eschatology of the Book of Revelation. Yet that fire and brimstone often seemed to fizzle down to a cold core of hypocrisy. The men who raged most vehemently against sin, who cried out the most passionately for repentance, seemed to be the most skillful at covering up their own crap.

Years later, when I first started writing erotica, I tried to put those Bible Belt memories behind me. It wasn’t so much that those threats of damnation made me feel guilty, but that they threatened my creative freedom. That televised Bible-thumping belonged to my past; I was living in the San Francisco Bay Area, getting my feet (and other parts) wet with sex-positive feminism, and conservative Christian morality wasn’t part of that new identity.

It took a few years of writing, finding a voice, before I was able to plunge into the well of the past, and when I dove in, I brought up a big dipperful of the Gospel. Strangely enough, I didn’t want to write against Christianity. I wanted to rewrite those experiences, giving them new endings, in which spiritual redemption was a matter of self-discovery, not self-denial. In stories like “Sex in the Pre-Apocalypse,” “Dirty White Shoes,” “The Book of Zanah,” and “Come for Me, Dark Man,” I fumbled around trying to articulate the idea that our sexuality—in whatever form it takes, whatever voice it speaks—is the physical manifestation of our divinity, and because of that, sex is good.

It took a few years of writing, finding a voice, before I was able to plunge into the well of the past, and when I dove in, I brought up a big dipperful of the Gospel. Strangely enough, I didn’t want to write against Christianity. I wanted to rewrite those experiences, giving them new endings, in which spiritual redemption was a matter of self-discovery, not self-denial. In stories like “Sex in the Pre-Apocalypse,” “Dirty White Shoes,” “The Book of Zanah,” and “Come for Me, Dark Man,” I fumbled around trying to articulate the idea that our sexuality—in whatever form it takes, whatever voice it speaks—is the physical manifestation of our divinity, and because of that, sex is good.

The wonderful thing about being a woman, a slut, and a perpetual child with unclean shoes is the way these act repeat themselves; you can hear the echo of those repetitions across acres of time. An anonymous screw remains as filthy and as joyous as ever; the fornicators of the world still constitute a rebel nation. You can wear your white shoes, in utter defiance of fashion, all the way to February, and some lady in the grocery store will still reprimand you for it. You can live like a whore, baring your tits and pussy to a tired world, and bask in the ancient light of damnation.

I wouldn’t say that the explosion of televangelism in the 1980’s turned me into a smut writer, though the prospect of burning naked over an eternal barbecue pit ignited a few fantasies. The sideshow tableaux of Hell and damnation didn’t offer me enough meat to feed any serious rebellion. What those TV preachers gave me, with their honey-coated condemnation of anyone who didn’t fuck members of the opposite sex in the missionary position within the bonds of holy matrimony, was motivation to cling to the fragments of Gospel as I understood it, and to live out that word according to my own twisted interpretation.

And I have to give thanks to Tammy Faye, a woman of God who was never ashamed to live out her vision of cosmetically challenged glamour, for inspiring me to take my fantasies public. Even in my shy, self-conscious adolescence, I felt a kinship with the outrageously overpainted Tammy; she clearly oozed something, but it wasn’t that cloying hypocrisy that seemed to taint so many of her cohorts. It was more like . . . sexuality. Raw, flamboyant, sluttish sexuality. And compassion. And strength. She was strong enough to survive the public scourging that followed the collapse of the Heritage USA empire, strong enough to survive marital infidelity and divorce, even strong enough to survive a makeover, and bounce back with her eyelashes thicker than ever. Though her soul had been saved by Jesus, she retained the design sense of a ho and the generous heart of a sinner:

her vision of cosmetically challenged glamour, for inspiring me to take my fantasies public. Even in my shy, self-conscious adolescence, I felt a kinship with the outrageously overpainted Tammy; she clearly oozed something, but it wasn’t that cloying hypocrisy that seemed to taint so many of her cohorts. It was more like . . . sexuality. Raw, flamboyant, sluttish sexuality. And compassion. And strength. She was strong enough to survive the public scourging that followed the collapse of the Heritage USA empire, strong enough to survive marital infidelity and divorce, even strong enough to survive a makeover, and bounce back with her eyelashes thicker than ever. Though her soul had been saved by Jesus, she retained the design sense of a ho and the generous heart of a sinner:

You can be part of that breed of gloriously misguided sinners who never could match their shoes to the seasons, one of those women who could never touch their lips to a teacup or a cock without leaving a ring of sticky scarlet lipstick. You can be one of us, if you're willing to be yanked out of your comfortable town. Remember, honey--it ain't the shit on your toes that matters, it's the height of your heels.

Thanks, Tammy Faye. I’ll miss you.

* * * *

Fiction excerpts from “Dirty White Shoes,” by Anne Tourney

Then he released her, letting his hand rest heavy on hers. She did not pull away. He felt her fingers beneath his on his prick, and he could have cried out for the torment and the pleasure of that touch.

Then he released her, letting his hand rest heavy on hers. She did not pull away. He felt her fingers beneath his on his prick, and he could have cried out for the torment and the pleasure of that touch.

Then there’s the exotic setting—see Bermuda, above. Anything could happen in this new and seductive place. You’re already on a grand adventure, your senses already stirred. Makes that much easier to get turned on, isn’t it? Back in college I met a boy in the walled medieval city of Avignon, on the night of a festival that involved the wild white horses of the Camargue being run through the narrow streets and wine being flung about to drench unsuspecting passersby. In a more mundane setting, I might not have looked at him twice, but in such a wild atmosphere, sparks flew that had very little to do with him and me and a lot to do with the exotic excitement of the night. (The wine, which was flowing liberally into us as well as into the gutters, helped, but those white horses really did me in.)

Then there’s the exotic setting—see Bermuda, above. Anything could happen in this new and seductive place. You’re already on a grand adventure, your senses already stirred. Makes that much easier to get turned on, isn’t it? Back in college I met a boy in the walled medieval city of Avignon, on the night of a festival that involved the wild white horses of the Camargue being run through the narrow streets and wine being flung about to drench unsuspecting passersby. In a more mundane setting, I might not have looked at him twice, but in such a wild atmosphere, sparks flew that had very little to do with him and me and a lot to do with the exotic excitement of the night. (The wine, which was flowing liberally into us as well as into the gutters, helped, but those white horses really did me in.)